Motivation

I wanted to build urv86t (short for the Ultimate RISC-V to x86 Transpiler) as a little toy-project to delve into the nasty business of binary format parsing, emulation, and cross-architecture recompilation. In particular, the weaknesses I wanted to reinforce within my knowledge were working with the LLVM ecosystem, and being able to put together a cohesive implementation of a non-trivial standard.

Technically, it would be more generally classifiable as a RISC-V to XY transpiler--LLVM-permitting--but my key focus wasn't to expand my knowledge of the x86 architecture; and, since LLVM appealed more in terms of its applicability to the wider field of compiler development, I opted to enroll into that learning curve instead.

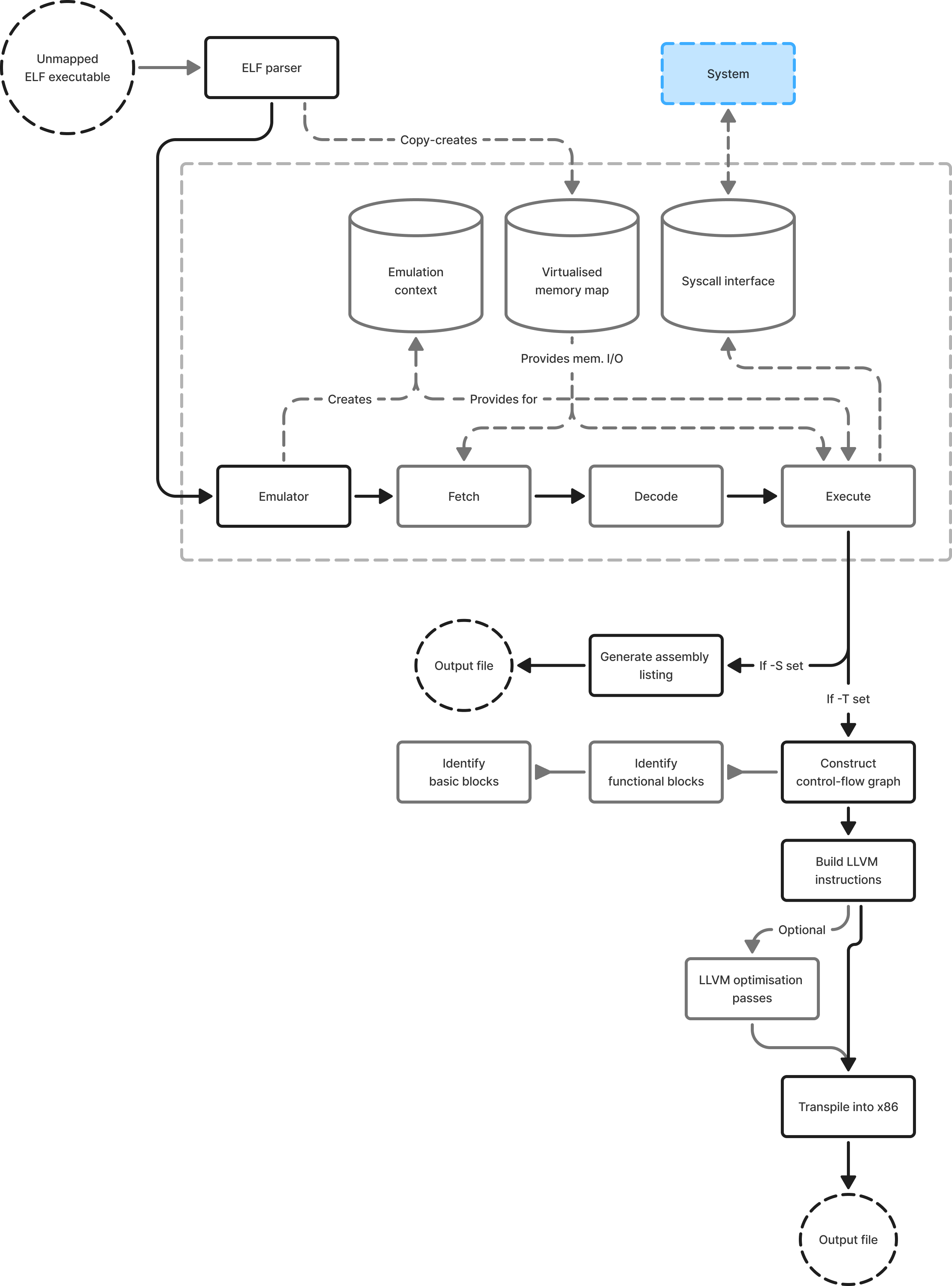

Architecture

A simplified version of the programming architecture is represented below. It resembles a simple Harvard-based emulation engine with an unpipelined single-core FDE-cycle working over a virtualised memory space generated by the ELF parser. Essentially, creating an emulation environment from an ELF executable.

Note that we must adhere to a few layers of ABIs/standard conventions within the implementation. The highest level is dictated by the RISC-V unprivileged specification, which determines the instruction/extension-level details, alignment constraints, etc.. Moving closer to software, various ABIs must also be specified for calling conventions (which subsequently gives proper names the registers,) and other details pertinent to the ELF/DWARF formats.

Emulation context

The Emulation Context store should be self-explanatory: necessary for the FDE-cycle to read/write state variables, like base/extension registers, a suspension flag, the program counter, and further metadata relevant for later stages.

ELF parser and virtualised memory map

The Virtualised memory map is supplemented by the ELF parsing stage, or more generally any pre-loading stage. It designates memory regions to the emulation engine, which then allow memory-accessing instructions to correctly map to the correct address in-memory. Below are the two relevant structural definitions:

struct elf_load_region

{

u32 vma_base;

u8* mem_base;

u32 sz_alloc, sz_reserved;

const char* tag;

};

typedef struct elf_context

{

struct elf_load_region* load_regions;

size_t nr_regions;

u32 entry_point;

u32 bp, sp;

} *elfctx_t;

bp and sp are stored fixed within the ELF context since they are typically defined after the memory mappings for the rest of the code/data are determined, though the actual stack pointers are managed in the ABI-specific base registers. Both the stack, and heap are also inserted into elf_context.load_regions, tagged with STACK/HEAP string identifiers respectively, otherwise regular memory regions are tagged as LOAD (following their ELF naming convention.) The heap makes special use of sz_alloc to determine the program break, indicating the number of bytes that have been considered meaningfully allocated from the vma_base.

When an instruction fetches from memory, the address is translated through a helper function:

u8*

elf_vma_to_mem (elfctx_t ctx, u32 ptr)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < ctx->nr_regions; ++i)

{

auto region = &ctx->load_regions[i];

if ((region->vma_base > ptr)

|| (ptr >= region->vma_base + region->sz_reserved))

continue;

return region->mem_base + (ptr - region->vma_base);

}

return NULL;

}

Which itself should be self-explanatory.

Misaligned, out-of-bound or illegal instruction fetches terminate the emulator outright, though it should be noted this should just modify the mcause control status register (CSR.)

System call interface

Since we're working with ELF executables, we should also try our best to emulate a Linux environment, since there doesn't appear to be any ABI specifications that detail RISC-V on PE executables. Therefore, systems calls should adhere to Linux's specifications detailed on the respective man page, which clarifies that the ecall instruction is used to invoke a system call, with arguments passed across a0 to a6, and return values in a0/a1 1.

The implementation for this is fairly trivial, simply passing through most basic system calls to their real counterpart, but become a little more complex such as in the case of brk:

RVSYSC_DEFN(rvsysc_brk, word_t brk)

{

auto heap = elf_get_heap_region (state->mem);

u32 min_brk = heap->vma_base,

current_brk = min_brk + heap->sz_alloc,

max_brk = heap->vma_base + heap->sz_reserved;

if (!brk)

return current_brk;

if ((brk < min_brk) || (brk > max_brk))

return current_brk;

heap->sz_alloc += brk - current_brk;

return brk;

}

Since we wish to use the heap designated by the virtual memory map and not our application's heap, we essentially need to reimplement a very watered down version of the actual system call. Due diligence for system call implementations should be taken when they may modify or interpret host system resources, unless otherwise allowed. This was a pivotal moment in the development of the emulator, since it allowed more comprehensive validation of the emulator's behaviour, given we could run real compiled binaries that utilised I/O system calls.

-

a0-a7refer tox10-x17, renamed by the ABI calling convention ↩